Introduction to problems: literacy

Posted 2020-10-03 14:37

Etiquette

Giving credit

This merits an immediate mention. When presenting a chess problem, always give credit to the composer(s). Failing to do so is at best impolite, and at worst downright plagiarism. Please, mention the composer(s), date and source of a problem as far as possible.

Also, provide the stipulation - let the solver know what the goal is! It is also an essential part of the problem.

Unpublished problems

If a composer shares an unpublished problem with you in private, do not repost it elsewhere. Putting up a problem in any sufficiently public domain (including publicly accessible websites, public internet forums or public mailing lists - see Article 20 of the Codex of Chess Composition) will count as a publication, rendering it ineligible for composing tourneys or as an original submission to problem magazines. Unpublished problems are still the property of the composer(s), so please respect this.

How to read

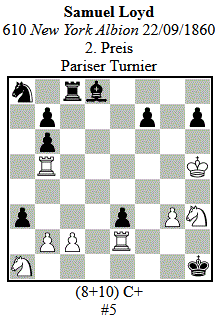

This is what a chess problem can look like in a publication or a database (the image was taken from Die Schwalbe PDB).

As you can see, there is a lot of information. Going through each part one by one:

- "Samuel Loyd" - the composer(s) of the problem.

- "610 New York Albion 22/09/1860" - where and when it was published. In general, at least the name of the publication (here it's the New York Albion newspaper) and the year of publication (1860) is given.

- "2. Preis, Pariser Turnier" - any awards or prizes the problem may have won (here, "2nd Prize" in a "Paris tournament"). It could be awards given out by the newspaper or magazine it was published in, or prizes won in a composing tournament it was specifically submitted to.

- [Board and pieces] - self explanatory! Referred to as "the diagram position" or simply "the diagram".

- "(8+10)" - the unit count of (white units + black units). A convenient way to verify that the position is correctly set up on a board or computer.

- "C+"" - if present, indicates that the problem has been verified to be sound by a computer (stands for "Computer check(ed)").

- "#5" - the problem stipulation, i.e. the objective for the solver. Here it is a directmate in 5 moves.

When sharing a problem, typically we convey at least the diagram, the stipulation and the composer(s).

Algebraic notation

If you're already a chessplayer familiar with algebraic chess notation, you just need to know that in problems, the symbol for the knight is S instead of N.

To describe pieces and moves, problemists use algebraic notation. Many publications today use figurine notation, which is mostly language-independent and internationally recognisable. If using pure text, then standard problemist algebraic notation is used. This is almost identical to standard English chess notation (see the FIDE Handbook, specifically the Laws of Chess), but with S as the symbol for the knight (from German Springer) instead of N, which is reserved for the Nightrider fairy piece.

See the table for a comparison of common algebraic notation variants used. A special mention goes to German notation, which the free Die Schwalbe problem database uses.

| Convention | Pawn | Knight | Bishop | Rook | Queen | King |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problems | (P) | S | B | R | Q | K |

| English | (P) | N | B | R | Q | K |

| German | (B) | S | L | T | D | K |

| French | (P) | C | F | T | D | R |

For fairy pieces, the choice of symbol is usually the obvious one, corresponding to the first letter of the piece name. In figurine notation, they are typically represented by 90-degree or 180-degree rotations of the most similar standard unit. Particularly well-known fairy pieces include the Nightrider (N) and the Grasshopper (G).

The symbols ? and ! are also sometimes used in notating solutions. ? indicates tries (moves that fail, and are not the solution), while ! indicates the key (solution move), or indicates defenses that defeat tries.

Stipulations

If you've played chess before, you may have already encountered directmates and studies, which are closest in nature to the game of chess.

Directmate (#n) : A regular "Mate in n" problem, e.g. "#3" means "mate in 3". By convention, White always moves first and tries to deliver mate by their n-th move; Black tries to avoid mate. : These are usually classified into twomovers (#2), threemovers (#3) and moremovers (#4 or longer).

Study (+ or =) : Usually endgame positions, where White to play has to find a way to win (+) or draw (=).

Also extremely common in the problem world are helpmates, selfmates, and reflexmates, as well as the series- condition. These extend chess beyond the adversarial, White-versus-Black game with alternating moves.

Helpmate (h#n) : Black moves first, and both sides cooperate such that Black is mated, e.g. "h#2" means "helpmate in 2"; both sides make moves black-white-black-white such that White's last move delivers checkmate. : Note that if the stipulation is "h#1.5" for instance, then the order of moves is white-black-white. : Helpstalemates (h=n) are similar, but both sides cooperate to stalemate Black.

Selfmate (s#n) : White forces Black to checkmate them, while Black tries to avoid delivering mate. By convention, White moves first.

Reflexmate (r#n) : A selfmate, but with the condition that both sides must play a mate in 1 if it is available at any point.

The series- condition (ser-) : The side to move makes n legal moves in a row, then the other side makes 1 move to meet the stipulation. For example, a serieshelpmate in 7 (ser-h#7) has Black play 7 moves in a row, then White makes 1 move to checkmate Black.

You may also encounter other genres of problem. Proof games and retros are major examples of heterodox problems without necessarily having fairy conditions or pieces (in contrast to the orthodox problems: directmates, helpmates and selfmates.)

Proof games (PG n) : From the regular chess starting position, both sides cooperate to play a legal game of chess that reaches the diagram position in n fullmoves. For instance, a "PG 8.0" reaches the diagram position after Black's 8th move; a "PG 5.5" reaches the diagram position after White's 6th move.

Retrograde analysis problems (varied stipulations) : Retro problems are a large class of problems with diverse stipulations, all based on logically deducing information about the position based on solely the diagram. For instance, a retro #2 could involve proving that the diagram position must have Black to move instead of White, or that an en passant key is legal because the move leading to the diagram must have been the double step of a pawn.

Anything else can generally be subsumed under the category of "fairy problems". This can be due to fairy pieces (pieces which move differently from the standard chess units, e.g. the Nightrider), fairy conditions (where the rules of the game are changed, e.g. Madrasi, where units attacked by their opposite colour counterparts cannot move), or both.

Twinning

Sometimes problems may have more than one part to solve, known as twinning. The different parts are usually indicated by letters. For example, "PG 7.0 a) Diagram b) bQd3 -> b3 c) bQd3 -> h4" tells you to first solve a proof game in 7.0 ending in the diagram position. Then in part (b), solve another PG 7.0 ending in the position with black's queen on b3 instead of d3. And in part (c), another PG 7.0 ending in the position with black's queen on h4 instead.

Many things can change in the twinning. Here are some of the more common types:

- Add pieces: "h#3 b) +wPa2"

- Remove pieces: "Last move? b) -wBf1"

- Move pieces (see example above)

- Change pieces: "h#2 b) bQa6 -> bRa6 c) bQa6 -> bBa6 d) bQa6 -> bSa6 e) bQa6 -> bPa6"

- Task: "#2 b) s#2"

- Fairy conditions: "#2 Circe b) Anti-Circe"

Help in looking up fairy pieces and conditions

The publication source of any particular fairy problem will usually include definitions of any fairy pieces or conditions used, e.g. in a summary page at the back of the publication issue. The StrateGems website lets you look up many fairy pieces and conditions. Christian Poisson also offers comprehensive definitions of fairy pieces, common fairy conditions, and not-so-common ones on his website.